When Small Things Records announced the death of singer songwriter, James Varda, at his home in Sheringham, Norfolk on 12 June 2015, there was a feeling that one of the most distinctive voices of his era had fallen silent.

He had lived and worked with a rare form of cancer for some time and, on Chance And Time, his astonishing final album, James chronicled the experience of confronting illness and death. In doing so, he created a unique language and music of love and pain, family, landscape and loss.

Chance And Time delivers an emotional insight like no other record. It is undoubtedly his best work.

Varda had first electrified audiences on the folk club circuit in the late-80s with songs like This Train Is Lost and Crawl In The Pen that seemed to draw from Tom Verlaine and Highway 61 era Dylan rather than English folk traditions. Fluid acoustic guitar fused with punk energy marked him out from a generation of golden-age wannabes. The folk clubs might have been uncertain, but they gave him gigs.

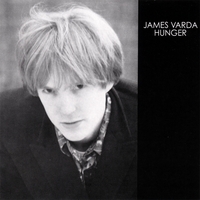

His status as an indie outsider led to an invitation to record with producer, John Leckie. The resulting album Hunger (1988) captured the immediacy of Varda’s live set. Here he recorded with musicians for the first time. As he recalled on the album’s CD reissue in 2008, ‘I’d always performed solo and I hadn’t rehearsed with the musicians so we just put the record together spontaneously in the studio. I think that’s why it still sounds fresh today.’

Leckie gave songs like Strange Weather a richer sound. Songs like Sunday Before The War and Just A Beginning, showcased Varda’s talent for arranging and performing with lone voice, guitar and harmonica. Lyrically, Hunger took a sideways look at the world. Varda didn’t like what he saw, but if his view seemed bleak, it was never entirely without redemption.

Music Week described Hunger as ‘Startling. Articulate. Passionate’. The momentum generated by its critical success saw Varda’s name added to that slim roster of those who make great music, but always and only on their own terms. He toured through 1988, supported Roy Harper, played Cambridge Folk Festival in 1989 and the Reading Festival in 1990. By then he might have expected to be recording a follow up to Hunger, but the vagaries of the music industry were taking their toll and he disappeared from public view. Like an acoustic Salinger, it seemed he’d said what he came to say.

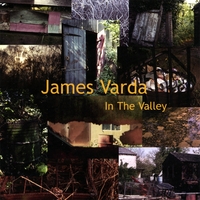

Leaving London for rural Suffolk, give or take the occasional live appearance, Varda was silent for a decade. The hiatus ended in 2004 with the album In The Valley. Interviewed for Time Out, he told Ross Fortune he’d used the break ‘to sort a few things out in my life’, and that he’d ‘never stopped writing songs’.

As an advert for quality control, it was hard to fault. In The Valley found Varda on great form, painting with a more refined acoustic palette. Songs like That’s The Time and Small Things suggested fresh perspectives on life. The melodies were delicate and the tone reflective. It was, said Tim Perry in the Independent, ‘a gorgeously mature work’. Time Out celebrated ‘a quietly wonderful return’.

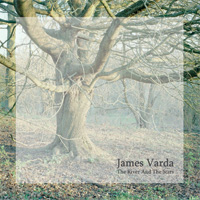

Cancer diagnosis and subsequent treatment meant that recording an immediate follow-up was out of the question. But Varda was living life. Always writing, he began crafting the songs that would eventually find their way onto The River And The Stars (2013). Inspired by the Suffolk landscape, tracks like Along The River are imbued with a heightened sense of the natural world. At its centre, Varda cast himself as the traveller with one eye on the horizon and changes in the weather. These are songs of summer turning to autumn, of dark nights and quiet desperation, of an enduring love that shouldn’t be taken for granted; songs of family, life’s fragility, of longing for peace and reconciliation with its absence.

Once again, the reviews acclaimed Varda’s return. R2 Rock n Reel acknowledged The River And The Stars as ‘a collection of songs that demands your attention’. Writing in Maverick Magazine, Alan Cackett lauded ‘a record of untold beauty’.

Varda had found musicians with whom he could translate his ideas into a musical reality. His voice is pure and true, but in the moment it catches on the album’s closing track, you sense that The River And The Stars is a letter to the future; a poem cut off mid-sentence, an unexpected fade out that leaves a question unanswered.

Sensing time was running out, Varda didn’t leave us waiting long for the response. If The River And The Stars was the sound of an artistic reawakening, Chance And Time found him reaching a creative peak. On every level, this an extraordinarily brave and beautiful piece of work. His writing was never more precise, nor delivering of a more telling emotional punch.

On the album’s release, he said, ‘Sometimes things fall into place. That’s what happened here. I think it’s the best collection of songs I’ve gathered together. There’s a cohesion and a completeness, an arc from beginning to end.’

Chance And Time carries a sense of things that need saying: from the sweet melodies and rare moments of May This Moment Ever Glow and Let My Place, to the cold reality of The Doctor Spoke and Only Love, Varda creates series of exquisite soundscapes. Pass It On delivers a love song to England, to love, to life and everything that is precious. Varda spins a universal truth from the intensely personal.

To paraphrase Townes Van Zandt, Varda always had to ‘sing for the sake of the song’. Bringing together musicians from The River And The Stars sessions, there’s a strong sense of a band coming together who buy into that ethos: Johanna Herron’s vocals melt perfectly into Varda’s on Our Love Will Never End; Fliss Jones’ piano on Beside The Sea is a piece of understated brilliance; and Nick Harper adds some great playing on One Thing After Another.

James Varda remained the acoustic outsider with indie sensibility. Absorbing the broadest of influences: New York new wave to Dylan and Philip Glass, the poetry of Jane Kenyon, the photography of Robert Adams, and dozens more; he always made great, thoughtful records with well-crafted lyrics and superb guitar. But here’s the skinny: at the end of his life, with Chance And Time, he produced one of the most powerful records of the last thirty years.

Nick Triplow, July 2015